Vol 4, No 1 (2026): Current Issue (Volume 4, Issue 1), 2026

Original Articles

Review Articles

Case Reports

The Barw Medical Journal is an online multidisciplinary, open-access journal with an extensive and transparent peer review process that covers a wide range of medical aspects. This Journal offers a distinct and progressive service to assist scholars in publishing high-quality works across a wide range of medical disciplines and aspects, as well as delivering the most recent and reliable scientific updates to the readers.

To maintain the quality of the Barw Medical Journal’s contents, a double-blind, unbiased peer-review process has been established and followed to only publish works that adhere to the scientific, technical, ethical, and standard guidelines. Barw Medical Journal focuses especially on the research output from developing countries and encourages authors from these regions of the world to contribute actively and effectively to the construction of medical literature.

We accept original articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, review articles, case reports and case series, editorials, letter to editors, and brief reports/commentaries/perspectives/short communications/correspondence. The journal mainly focuses on the following areas:

- Evidence-based medicine.

- public health and healthcare policies.

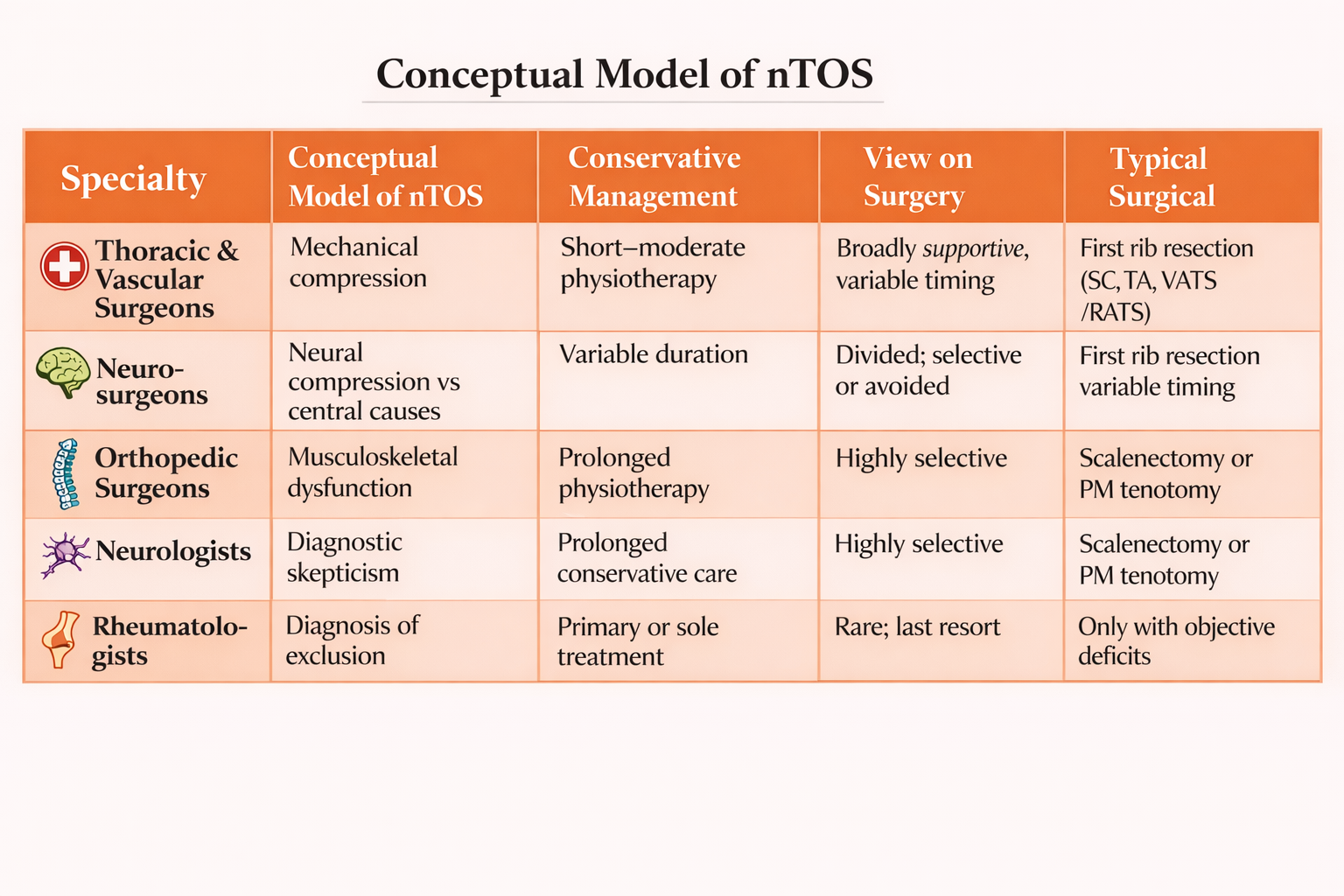

- Current diseases’ diagnosis and management.

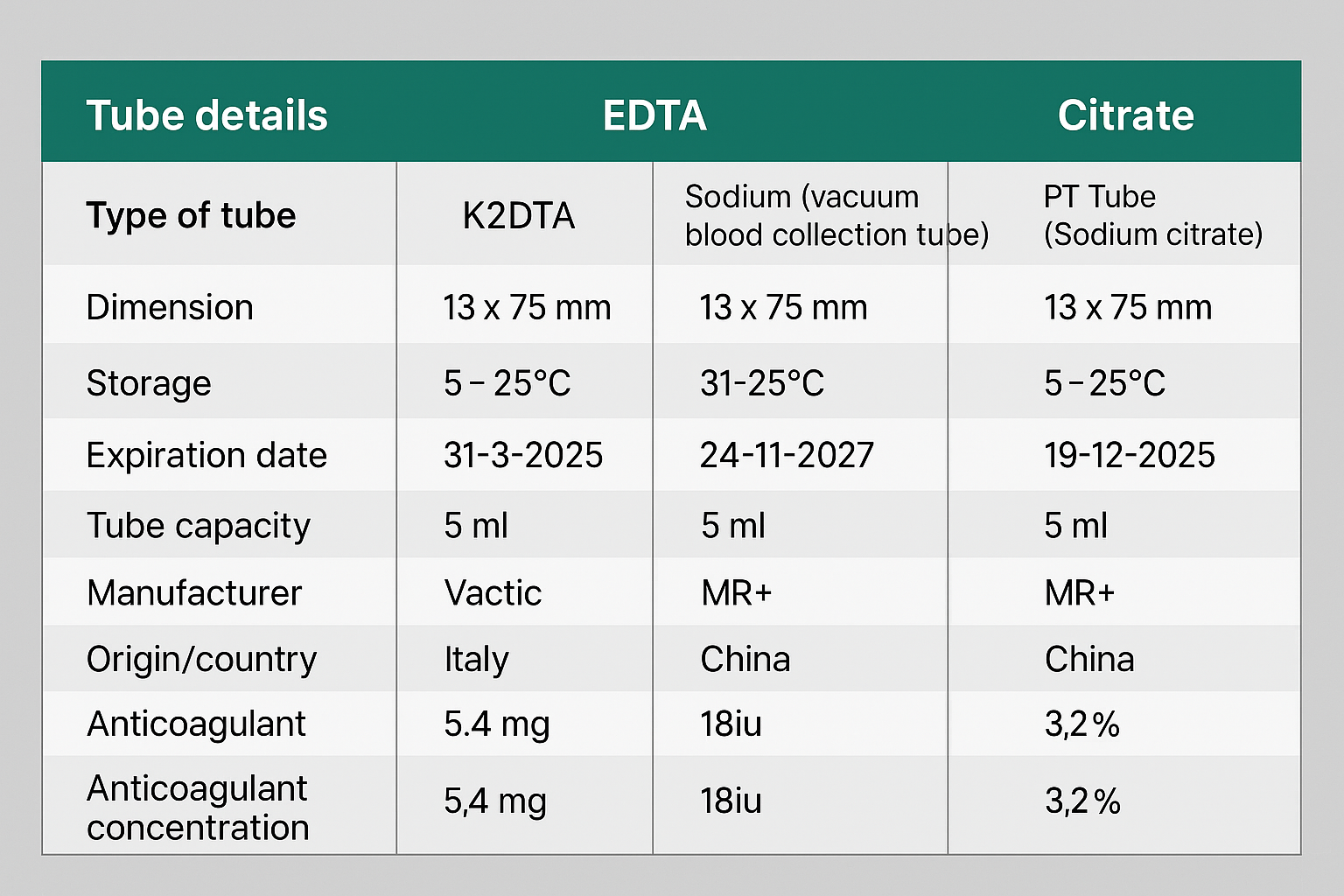

- Biomedicine, including physiology, genetics, molecular biology, pharmacology, pathology, and pathophysiology.

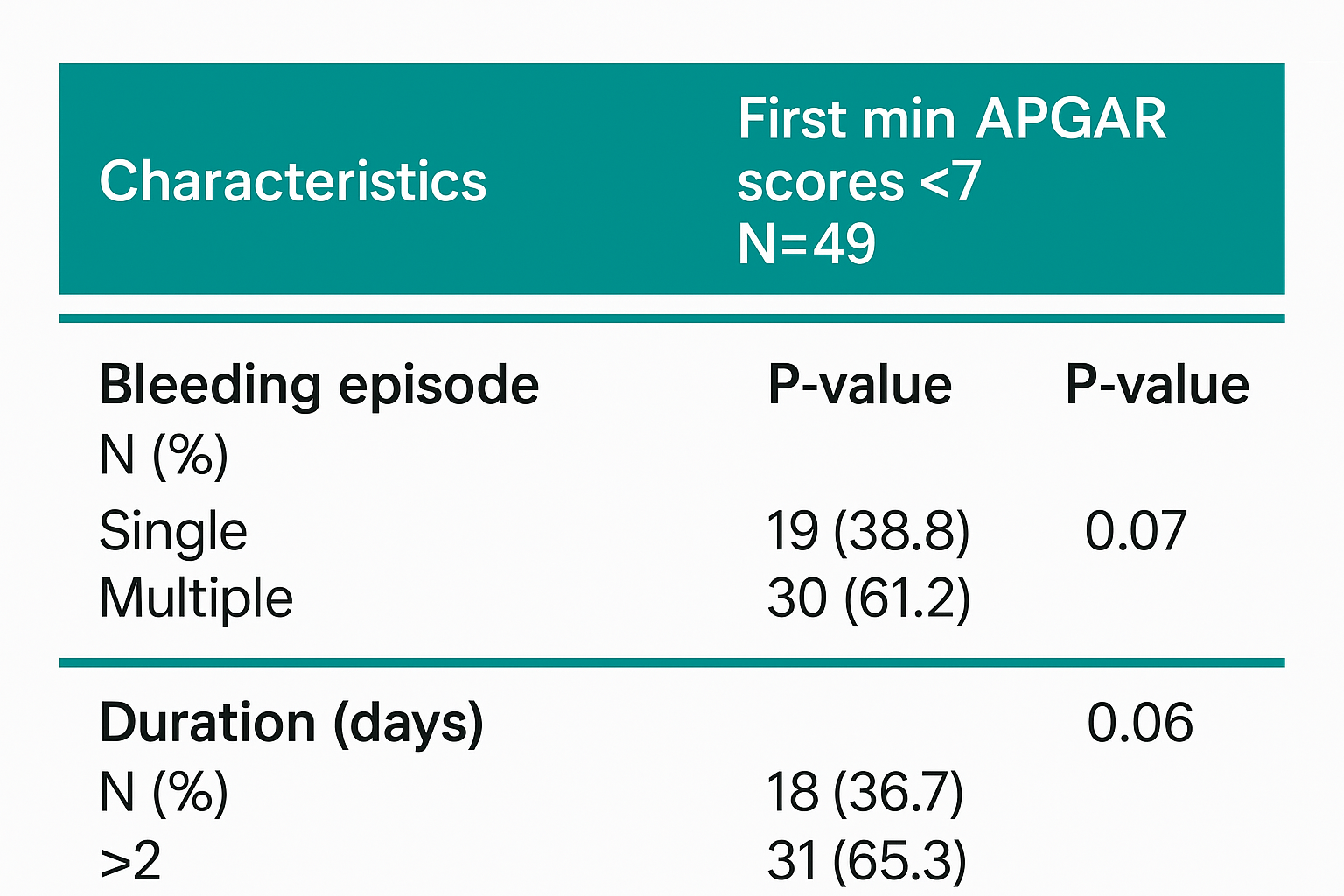

- Clinical and applied studies like surgery and innovated techniques, internal medicine, gastroenterology, obstetrics, gynecology, pediatrics, and otorhinolaryngology.

Latest Articles